If you know anything about mammals, you’ll know that crown-mammals – modern mammals – fall into three main groups: the viviparous marsupials and viviparous placentals (united together as therians), and the egg-laying monotremes. The fact that monotremes lay eggs is familiar to us today, but of course it was a huge surprise when first discovered. There’s a whole story there which I won’t be recounting here.

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 8 (THE LAST PART)

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 7

Welcome to part – oh my god – seven in this seemingly eternal series.

Like me, I’m sure you want it to end so I can get back to writing about the innumerable other things on the list. Yes, we’re here, once again, for another instalment in the Too Many Damn Dinosaurs (TMDD) series. If you’re new to the whole thing, go back to Part 1 and see what this is all about; if you want to see all previous parts in the series go to the bottom of the article for the links (or use the sidebar). In the most recent articles, we looked at two assumptions inherent to the TMDD contention: that sauropod populations were similar in structure to modern megamammal populations, and that sauropods and other big dinosaurs were similar to Holocene megamammals in ecology and distribution. Here, we look at a third assumption, and it’s one that just won’t die.

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 6

Oh wow, we’re at Part 6 in the Too Many Damn Dinosaurs (TMDD) series already. You’ll need to have seen at least some of the previous articles to make sense of this one: you can either follow the links below, or click through the links in the sidebar. In Part 5 we looked at the first of a series of assumptions made by those who’ve advocated the TMMD contention; namely, that Late Jurassic sauropods had a population structure similar to that of megamammals. In this article, we look at a second assumption…

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 5

If you’ve been visiting TetZoo over recent weeks, you’ll know why we’re here. Yes, we’re here to continue with the Too Many Damn Dinosaurs (TMDD) series, in which I argue that it’s wrong to argue – that is, on principle, rather on detailed evaluation of the evidence – that the world famous Late Jurassic Morrison Formation contains too many sauropods. In the previous four parts of this series we introduced the DMDD contention, we looked at the fact that Paleogene mammals are not especially relevant to the TMDD contention, and then at the fact that modern giraffes are not especially relevant to the TMDD contention either.

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 4

In the previous articles in this series (see part 1 here, part 2 here and part 3 here) we looked at the ‘too many damn dinosaurs’ (TMDD) contention, this being the claim that the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation simply has too many sauropod dinosaurs. You’ll need to check those previous articles out before reading this one. The previous parts of the series introduce the TMDD contention and then discuss whether arguments made about Paleogene fossil mammals and modern giraffes are relevant. Here, we move on to something else.

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 3

Welcome to the third part in this lengthy series of articles, all of which are devoted to the argument that those Mesozoic faunas inhabited by multiple sauropod taxa – in particular those of the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation – have too many damn dinosaurs (TMDD!). You need to have read parts 1 and 2 for this to make sense. Those articles set up the TMDD contention, and then showed why arguments relating sauropod diversity to Paleogene mammal diversity are erroneous. In this article, we look at another mammal-based argument.

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 2

A few authors would have it that there are too many damn dinosaurs (TMDD!): that the rich sauropod assemblage of the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation of the continental western interior of the USA simply contains too many species, and that we need to wield the synonymy hammer and whack them down to some lower number. In this article and those that follow it, I’m going to argue that this view is naïve and misguided. You’ll need to have read Part 1 – the introduction – to make sense of what follows here. Ok, to business…

Stop Saying That There Are Too Many Sauropod Dinosaurs, Part 1

Professor Jenny Clack, 1947-2020

Within recent decades, four specific areas of palaeontological discovery and reinterpretation have succeeding in capturing mainstream attention: the feathering of dinosaurs, the evolution of hominins, the early history of whales, and the early evolution, anatomy and biology of the earliest tetrapods. And it’s the last of those subjects we’re focusing on here. It’s a subject which has seen regular airing in top-tier journals, science magazines and TV documentaries, and one which has undergone a major and exciting revolution since the 1980s.

Caption: at left, Professor Jenny Clack, in the field at Burnmouth in the Scottish Borders. At right: in 2017, Jenny and her husband Rob got to fly in a Spitfire. Images: (c) Rob Clack, used with permission.

One person above all others has been responsible for leading research in this field and has made numerous ground-breaking discoveries herself, both in the field and laboratory. I am of course referring to Professor Jenny Clack of the Department of Zoology at the University of Cambridge, an excellent and highly respected scientist whose technical papers are authoritative, ground-breaking and of the highest standard. Her publication list is formidable. Alas, I regret to write that I’m here for sad reasons, since Jenny died on the morning of 26th March 2020 following a five-year struggle with cancer. While – for my shame – I haven’t written about early tetrapod evolution here at TetZoo before, nor about Jenny’s research specifically, both are areas I’ve avidly followed, and I want to share some brief thoughts here.

Caption: a selection of Clack publications in the TetZoo library. Image: Darren Naish.

Prior to Jenny’s work, the consensus view on the oldest tetrapods – in particular Ichthyostega from the Devonian of Greenland – is that these were ‘terrestrialised’, vaguely salamander-like quadrupeds, well able to walk on land by planting all four feet on the substrate. This view, entrenched in textbooks and the popular literature, mostly owed itself to the work of Swedish palaeontologist Erik Jarvik whose work on Ichthyostega, while initiated in the 1950s, took some decades to appear, finally being published in 1996. Jarvik’s work has its own long and curious backstory (Ries 2007) – which I can’t cover here – and it certainly wasn’t missed by some of us that the conclusions of his supposedly definitive monograph were being called into doubt just weeks after its appearance (Norman 1996).

Caption: Jenny Clack (and Professor Robert Insall) at the Ballagan Formation type locality, near Glasgow. Image: (c) Rob Clack, used with permission.

Tantalising remains of an Ichthyostega contemporary – the smaller Acanthostega – were discovered in East Greenland on a Cambridge University expedition of 1970 (and were languishing, unrecognised, in the drawers of the university’s earth sciences department prior to Jenny’s interest). These indicated that, with luck, more early tetrapod finds might be discovered in the same region. After making special arrangements with Danish scientists – and with Jarvik, who the Danes wanted to remain on good terms with – Jenny visited Greenland in 1987; she was accompanied by colleagues from Copenhagen, her husband Rob and her then PhD student Per Ahlberg (Clack 1988). They were remarkably successful, retrieving multiple good specimens, and continued to be so on later trips to the same region.

Caption: in more recent years, it’s become obvious that Ichthyostega - the classic ‘early tetrapod’ - was not just a formidable, toothy predator, but an unusual, specialised animal with paddle-like hindlimbs, a proportionally short tail and a regionalised vertebral column. Image: Ahlberg et al. (2005).

Was Jarvik right about these animals? Not really, no. The discovery of numerous aquatic specialisations in Ichthyostega and the smaller Acanthostega – published by Mike Coates and Jenny during the early 1990s (Coates & Clack 1990, 1991) – was a huge surprise. Tetrapods didn’t start their history as land-walking animals with pentadactyl hands and feet, as Jarvik (and just about everyone else) had thought, but were aquatic and polydactyl, with 8 fingers and 7 toes (or thereabouts)! Later work showed that Ichthyostega had an unusual ear perhaps specialised for aquatic hearing (Clack et al. 2003) and a remarkable regionalised vertebral column and other peculiarities (Ahlberg et al. 2005) suggesting that, when on land, it might have moved in mudskipper-like fashion (Ahlberg et al. 2005, Pierce et al. 2012, 2013).

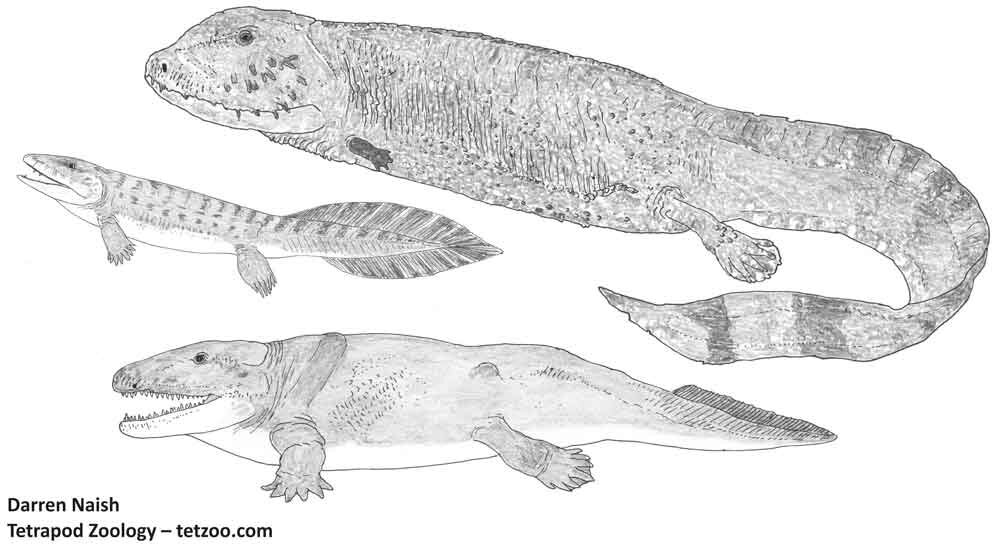

Caption: life reconstructions of three early tetrapods worked on by Clack: the big Crassigyrinus, the small, aquatic Acanthostega, and the big (c 1 m long) Ichthyostega. These images are among tens of archaic tetrapods reconstructed for my in-prep textbook. I’ve learnt recently that the Crassigyrinus will soon need revising. Image: Darren Naish.

Jenny’s work wasn’t limited to this fundamental reinterpretation of the earliest tetrapods, but also involved taxa from throughout the Devonian and Carboniferous. She revised knowledge of the remarkable aquatic Carboniferous tetrapod Crassigyrinus (Clack 1998a), described the new species Eucritta melanolimnetes (Clack 1998b), Pederpes finneyae (Clack 2002a, Clack & Finney 2005), Kyrinion martilli (Clack 2003) and others, reported entire new faunal assemblages (Clack et al. 2016) and published key interpretations of such groups as embolomeres (Clack 1987, Clack & Holmes 1988), chroniosuchians (Clack & Klembara 2009, Klembara et al. 2010) and microsaurs (Clack 2011). This extensive, substantial experience made her the right person to publish an authoritative and comprehensive book on Devonian and Carboniferous tetrapods: Gaining Ground: The Origin and Evolution of Tetrapods appeared in 2002 (Clack 2002). It went to second edition in 2012. It’s the best guide to early tetrapod evolution and fills a much-needed gap in the semi-technical literature, and I strongly recommend it to those interested in the subject.

Caption: covers of the first and second editions of Clack’s Gaining Ground. The cover images are, respectively, by Jenny Clack and Julia Molnar. The Clack image shows two individuals engaging in courtship: the green hump at the back left is the body of a second animal.

I never had the privilege of working with Jenny or of accompanying her in the field, but I did have reason to speak to her on several occasions, and to correspond with her. She was friendly and generous with her time and went to trouble to provide me with information and illustrations on an occasion when email wasn’t doing its job. It’s also obvious that she had a sense of humour. Of those new species listed above, Eucritta melanolimnetes translates roughly as ‘creature from the black lagoon’. Some – probably all – of the Ichthyostega and Acanthostega specimens she discovered in Greenland had nicknames: I’m pretty sure I recall seeing that one of them was called Grace Jones. Those who knew her so much better confirm that she was excellent fun, a great leader in the field, and a brilliant mentor.

Caption: several of the archaic Devonian tetrapods study by Clack and her colleagues are excellent, 3D and with very detailed preservation. This image shows an Acanthostega gunnari cast at Musee De L'Histoire Naturelle, Brussels. Image: Ghedoghedo. CC BY-SA 3.0 (original here).

Jenny began her scientific career during the early 1970s and received her PhD at the University of Newcastle Upon Tyne in 1984 under Alec Panchen. Panchen initially offered her a PhD following anatomical discoveries she made while preparing the notoriously difficult holotype specimen of the Carboniferous embolomere Pholiderpeton, initially described by Thomas Huxley in 1869. She joined the University of Cambridge in 1981 and for more than ten years was Assistant Curator at the University’s Museum of Zoology, later being promoted to Senior Assistant Curator and then Curator. She supervised a number of people who went on to become well known in vertebrate palaeontology and evolutionary biology, among them Mike Lee (whose PhD was specifically on pareiasaurs), sauropod expert Paul Upchurch, and actinopterygian fish worker Matt Friedman.

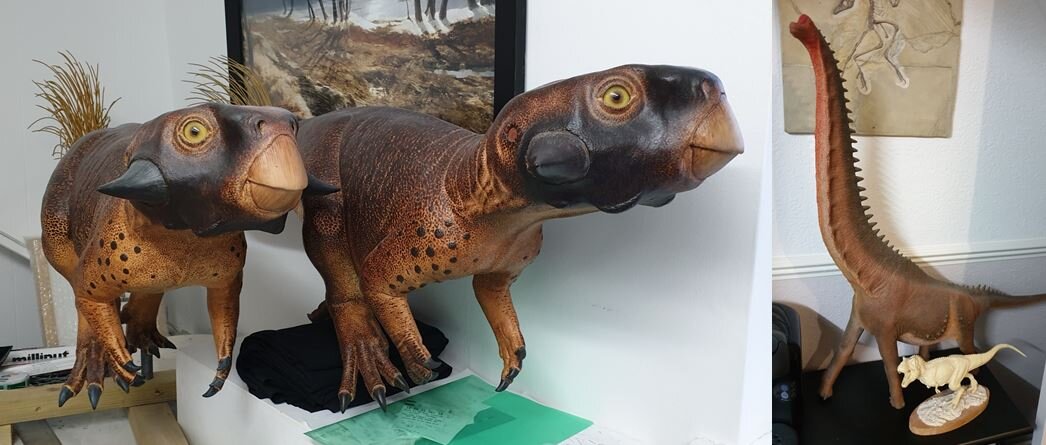

Caption: life-sized models of Ichthyostega and Acanthostega have been made a few times. Here’s the Acanthostega on show at the Sedgwick Museum, Cambridge. I’ve photographed this model several times but none of my photos are that good - I stole this image from Christian Kammerer (source).

Jenny retired in 2015. As you might expect give her scientific achievements, she was highly decorated, holding several palaeontological medals, additional, honorary doctorates and other awards too. Such was mainstream interest in her work and ideas that a 2012 episode of the BBC series Beautiful Minds was devoted to her (it’s viewable here on youtube); among other interesting things, it reveals that she was inspired during her childhood years by newts and freshwater fishes, and that it was learning about Mary Anning which encouraged her to pursue palaeontology. She liked motorbikes and cats, and some of the documentaries that focus on her work show her riding around on her motorbike.

Caption: the Tournaisian rocks of Burnmouth, north of Berwick-upon-Tweed, have, within recent decades, proved an important new locality for tetrapods. As a consequence, Jenny and colleagues set up the TW:eed Project, the acronym standing for Tetrapod World: Early Evolution and Diversity. Jenny (in the green top) stands close to the middle. Image: (c) Rob Clack, used with permission.

My text here only touches on a few aspects of her achievements, life and technical contributions, and I know that much else could be said. I’m very saddened to hear of her passing, very much regarded her as an excellent scientist who published exciting research, and I’ll miss her as a regular attendee of palaeontological meetings. My sincere condolences to her husband Rob, and to those others who knew and loved her.

Some of the text here is adapted from my in-prep giant textbook on the vertebrate fossil record.

The University of Cambridge website on Professor Clack is here

An excellent website on Professor Clack’s research and expeditions is here

Refs - -

Ahlberg, P. E., Clack, J. A. & Blom, H. 2005. The axial skeleton of the Devonian tetrapod Ichthyostega. Nature 437, 137-140.

Clack, J. A. 1987. Two new specimens of Anthracosaurus (Amphibia: Anthracosauria) from the Northumberland coal measure. Palaeontology 30, 15-26.

Clack, J. A. 1988. Pioneers of the land in East Greenland. Geology Today 4 (6), 192-194.

Clack, J. A. 1998a. The Scottish Carboniferous tetrapod Crassigyrinus scoticus (Lydekker) – cranial anatomy and relationships. Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences 88, 127-142.

Clack, J. A. 1998b. A new Early Carboniferous tetrapod with a mélange of crown-group characters. Nature 394, 66-69.

Clack, J. A. 2002a. An early tetrapod from 'Romer's Gap'. Nature 418, 72-76.

Clack, J. A. 2003. A new baphetid (stem tetrapod) from the Upper Carbinoferous of Tyne and Wear, U.K., and the evolution of the tetrapod occiput. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 40, 483-498.

Clack, J. A. 2011. A new microsaur from the Early Carboniferous (Viséan) of East Kirkton, Scotland, showing soft tissue evidence. Special Papers in Palaeontology 86, 45-55.

Clack, J. A., Ahlberg, P. E., Finney, S. M., Dominguez Alonso, P., Robinson, J. & Ketcham, R. A. 2003. A uniquely specialized ear in a very early tetrapod. Nature 425, 65-69.

Clack, J. A., Bennett, C. E., Carpenter, D. K., Davies, S. J., Fraser, N. C., Kearsey, T. I., Marshall, J. E. A., Millward, D., Otoo, B. K. A., Reeves, E. J., Ross, A. J., Ruta, M., Smithson, K. Z., Smithson, T. R. & Walsh, S. A. 2016. Phylogenetic and environmental context of a Tournaisian tetrapod fauna. Nature Ecology & Evolution 1: 0002.

Clack, J. A. & Finney, S. M. 2005. Pederpes finneyae, an articulated tetrapod from the Tournaisian of western Scotland. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 2, 311-346.

Clack, J. A. & Holmes, R. 1988. The braincase of the anthracosaur Archeria crassidisca with comments on the interrelationships of primitive tetrapods. Palaeontology 31, 85-107.

Clack, J. A. & Klembara, J. 2009. An articulated specimen of Chroniosaurus dongusensis and the morphology and relationships of the chroniosuchids. Special Papers in Palaeontology 81, 15-42.

Coates, M. I. & Clack, J. A. 1990. Polydactyly in the earliest known tetrapod limbs. Nature 347, 66-69.

Coates, M. I. & Clack, J. A. 1991. Fish-like gills and breathing in the earliest known tetrapod. Nature 352, 234-236.

Klembara, J., Clack, J. A. & Čerňanský, A. 2010. The anatomy of palate of Chroniosuchus dongusensis (Chroniosuchia, Chroniosuchidae) from the Upper Permian of Russia. Palaeontology 53, 1147-1153.

Norman, D. 1996. [Review of] The Devonian tetrapod Ichthyostega. Palaeontological Newsletter 31, 13-15.

Pierce, S. E., Ahlberg, P. E., Hutchinson, J. R., Molnar, J. L., Sanchez, S., Tafforeau, P. & Clack, J. A. 2013. Vertebral architecture in the earliest stem tetrapods. Nature 494, 226-229.

Pierce, S. E., Clack, J. A. & Hutchinson, J. R. 2012. Three-dimensional limb joint mobility in the early tetrapod Ichthyostega. Nature 486, 523-526.

Ries, C. J. 2007. Inventing ‘the four-legged fish’. The palaeontology, politics and popular interest of the Devonian tetrapod Ichthyostega, 1931-1955. Ideas in History 2, 37-78.

Theropod Dinosaurs of the English Wealden, Some Questions (Part 1)

I have no idea whether I’m known for being a specialist on anything. But of the several zoological subject areas I publish on, among my favourite and most revisited is the dinosaurs of the English Wealden, and in particular the theropods (that is, the predatory dinosaurs) of the English Wealden.

At left: a Wessex Formation scene, depicting Eotyrannus, a compsognathid (at lower right), a pachycephalosaurian Yaverlandia in the middle distance, and the titanosauriform ‘Angloposeidon’. I need to do some new Wealden dinosaur artwork. At right: a younger, slimmer version of this blog’s author, holding the holotype claw of Baryonyx walkeri in 2001 or thereabouts. Images: Darren Naish.

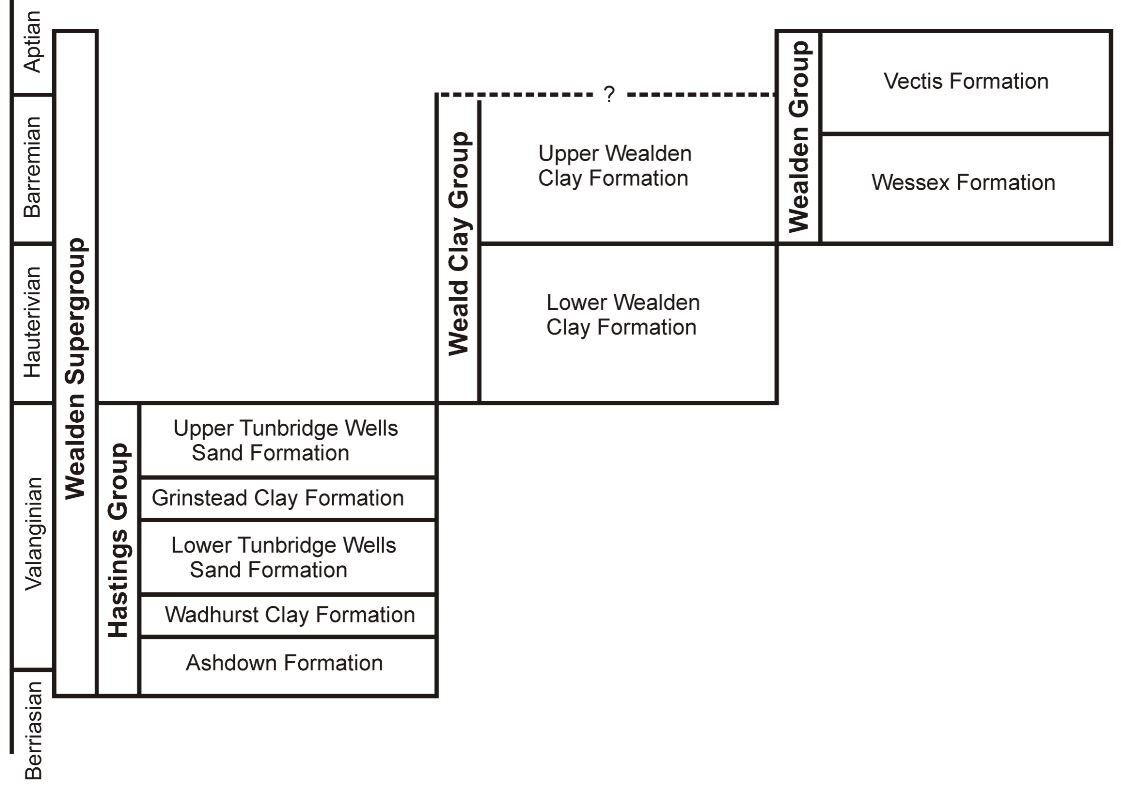

What is the Wealden? It’s a Lower Cretaceous succession – formed of sandstones, siltstones, mudstones, limestones and clays – which was deposited during the Early Cretaceous, its oldest layers being from the Berriasian (and thus about 143 million years old) and its youngest from the early Aptian (and thus about 124 million years old). The sedimentology, subdivisions and terminology of the Wealden are complicated, but all you need to know here is that the whole lot is termed the Wealden Supergroup, that it has an old section called the Hastings Group and a younger section called the Weald Clay Group – both of which crop out on the English mainland – and that there’s also a young section called the Wealden Group that mostly crops out on the Isle of Wight. Finally, you also need to know that the Wealden Group includes the Wessex and Vectis formations. Yikes, even that brief summary was complicated, sorry.

Simplified stratigraphic nomenclature of the Wealden Supergroup. Note that the Hastings Group is much older than the Weald Clay and Wealden groups. The vast majority of Wealden dinosaurs come from the Wessex Formation. Image: Naish (2010).

The really interesting thing about the Wealden is that it’s highly fossiliferous, yielding everything from pollen and diatoms to dinosaurs. Wealden dinosaurs have been hugely important to our evolving understanding of these animals, in part because some of the earliest discoveries – Iguanodon, Hylaeosaurus and Hypsilophodon among them – come from the Wealden succession. Many Wealden dinosaurs have also been famously vexing, in part because they were discovered at a comparatively early stage in our knowledge, in part because their remains have been (and still are) highly incomplete, and in part because their historical taxonomy is a convoluted nightmare. Note also that the circa 20 million year duration of the Wealden means that its dinosaurs were not all contemporaries. Instead, they belonged to a series of distinct faunal assemblages. Within the last few decades, the Wealden has – focusing here on theropods alone – yielded the superstars Baryonyx, Neovenator and Eotyrannus, and its potential to give us really spectacular finds even today is affirmed by additional theropods that are yet to be published.

The Wessex Formation allosauroid Neovenator - here shown with some of its facial bones in partial x-ray - was covered here at TetZoo (ver 3) back in 2017. Our conclusions on the facial anatomy of this dinosaur (Barker et al. 2017) have since been challenged. Image: Darren Naish.

While I could say a whole lot more (I’ve co-authored a whole book on Wealden dinosaurs: Martill & Naish 2001), the point of the article here (and its follow-up, to be published later) is to provide a progress report of sorts on a few contentious or in-prep areas of Wealden theropod research. And I’ll admit right now that the topics I cover here are unashamedly based on my own research interests and projects, sorry. To work…

At left, Martill & Naish (2001) (cover art by Julian Hume). At right, Batten (2011), truly a must-have volume on Wealden palaeontology. Martill & Naish (2001) is now hard to get and only sold at ridiculous prices.

What are you, Yaverlandia? In 1923, Mr F. M.G. Abell discovered the partial skull roof of a fossil reptile at Yaverland on the Isle of Wight. Its thickened bone immediately led Watson (1930) to suggest that it might be from a pachycephalosaur. Fast forward now to the 1970s: Peter Galton – at the time, revising and redescribing all British ornithischians – took this idea and ran with it. He formally named the specimen Yaverlandia bitholus and argued that it was indeed a pachycephalosaur, the most archaic known (Galton 1971). This became the standard take on this dinosaur and the one I supported when writing Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight in 2001 (Naish & Martill 2001).

At top, the Yaverlandia holotype in (left) ventral and (right) dorsal view. Below, the source of shame. Images: Darren Naish.

During my PhD years I was inspired to think about Yaverlandia anew, mostly because Jim Kirkland and Robert Sullivan (busy at the time with pachycephalosaurs) were pushing the idea that Galton’s identification was very likely wrong. I borrowed the specimen, produced a redescription, had the specimen CT-scanned, and photographed it to death. And I discovered a bunch of new stuff, all of which convinced me that Yaverlandia was not a pachycephalosaur at all, but a theropod. This data formed a chapter of my PhD thesis and brief summaries of my conclusions have been made here and there, including at conferences and in Naish (2011).

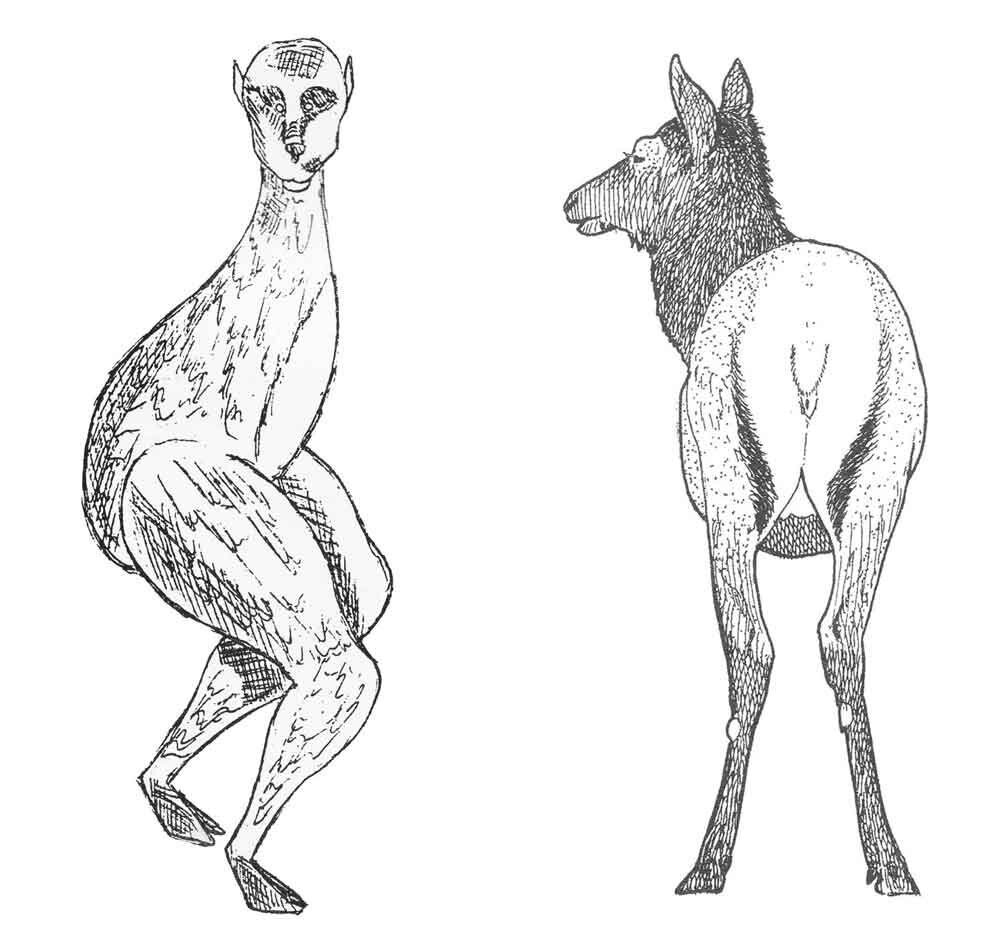

Life reconstructions of Yaverlandia are few and far between. This one (seeming to show the animal in a quadrupedal pose: note how the artist has hidden the hand, a classic case of trying to cover up a mistake) is from the fabled Orbis part-work magazine series. I think (but can’t confirm) that the artist was Jim Channel. Image: (c) Orbis.

But the full, detailed explanation of the theropod hypothesis hasn’t yet appeared, though I promise that it will eventually (it’s a work I’m co-authoring with Andrea Cau). As is so often the case with my academic projects, I haven’t been able to make time to finish it (insert reminder about all my academic research being unfunded and done in ‘spare time’: I am not employed in academia). I should also add that a second specimen of Yaverlandia is known and also awaits writing-up. That’s a study I’m doing with Steve Sweetman.

It’s well known in the theropod research community that the full description of this amazing fossil - the holotype of the Spanish ornithomimosaur Pelecanimimus - was done back in the 1990s [UPDATE: nope, 2004], but hasn’t seen print for a bunch of reasons. Consequently, good information on the specimen isn’t (yet) available. Despite that, this photo has been widely shared online. I don’t know who to credit for it.

Are there ostrich dinosaurs in the Wealden or not? Back in the day, I was thrilled by the 1994 description of the remarkable multi-toothed ornithomimosaur Pelecanimimus polyodon from the Barremian Calizas de La Huérguina Formation of Spain. Not just because it’s a neat dinosaur, but because the Calizas de La Huérguina Formation has a lot in common with the Wealden: the two share a list of amphibians, mammals, lizards, crocodyliforms and dinosaurs, this rendering it plausible or likely that Pelecanimimus (or a similar taxon) might await discovery in the Wealden too (Naish et al. 2001, Naish 2002). Predicting the presence of a given group in a given faunal assemblage is a cheap and easy thing to do, and you can award yourself points for prescience and smarts if you’re proved right (even though most people will ignore your prediction), and no-one cares or notices if you never are. So, I’m not looking for a Wealden cookie here. Whatever, “where are the Wealden ornithomimosaurs?” was a question on my mind for a while.

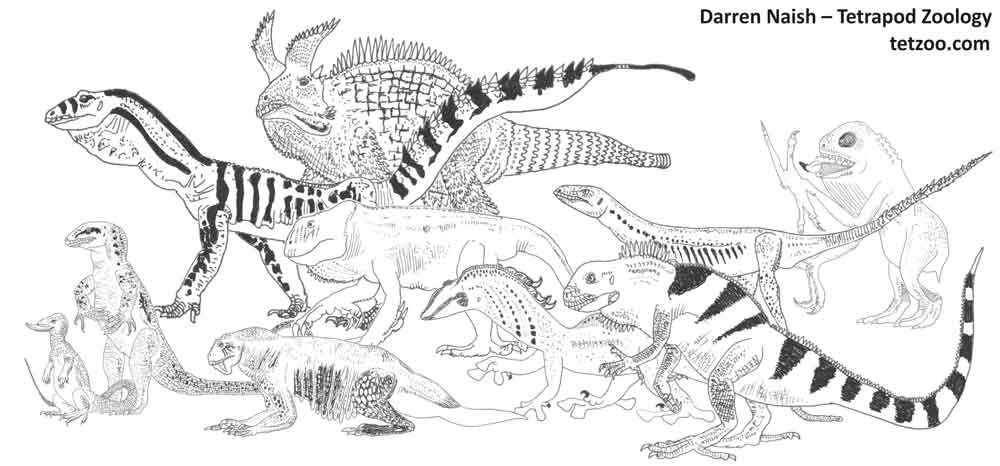

These drawings - produced for Dino Press magazine back in 2002 - look very dated now. They’re supposed to show those smaller theropod groups confirmed for the Wealden (at top) and predicted for the Wealden but still awaiting discovery (at bottom). Images: Darren Naish.

So, I was pretty happy when – in 2014 – Ronan Allain and colleagues announced their discovery of such creatures in the Wealden. They’d discovered a new theropod in the Lower Cretaceous of France (specifically, in the Hauterivian or Barremian of Angeac in Charente, southwestern France) and had used this as a ‘Rosetta Stone’ in the interpretation of other Lower Cretaceous European theropod fossils (Allain et al. 2014). Several Wealden theropods – Valdoraptor, the Calamosaurus tibiae and Thecocoelurus among them – were ornithomimosaurs according to this study (Allain et al. 2014).

In 2014, I superimposed an ornithomimid into the Wessex Formation scene you saw above… this effort was not meant to be entirely serious (and an ornithomimid is the wrong kind of ornithomimosaur anyway). Image: Darren Naish.

I was initially enthusiastic about this proposal and thought that the authors were likely right. But as more and more information has been released on the Angeac theropod, the less like an ornithomimosaur it seems. It looks, instead, like a noasaur. Furthermore, the assorted relevant Wealden remains aren’t as similar to the bones of the Angeac animal as initially argued (Mickey Mortimer pointed this out in an article of 2014). Proper evaluation of what’s going on here will have to wait until a full description of the Angeac theropod appears in print. But if the Angeac theropod is a noasaur, the possibility that it’s close to or congeneric with one or more Wealden theropods remains a likelihood: Thecocoelurus (named for a single cervical vertebra from the Wessex Formation) looks like a noasaur vertebra (Naish 2011)... though that doesn’t necessarily mean that it is (since it also looks like an oviraptorosaur or therizinosaur vertebra in some features).

Mickey produced this image for a 2014 article at The Theropod Database (here).

To bring this round full circle, we might still be missing those predicted Wealden ornithomimosaurs.

Are there other Wealden tyrannosauroids besides Eotyrannus? Loooong-time readers of my stuff – I mean, those who’ve been visiting TetZoo since 2006 – might remember my suggestion from way back that some of the smaller theropod specimens from the Wealden are sufficiently similar to tyrannosauroids from the Lower Cretaceous of China to perhaps be additional small-bodied members of this group. I’m talking about Calamosaurus foxi (named for two cervical vertebrae), Aristosuchus pusillus (named for a partial pelvis and sacrum) and a few additional bits and pieces, including the so-called Calamosaurus tibiae (note the plural there). If these remains do belong to tyrannosauroids, they’re from taxa distinct from Eotyrannus (which everyone agrees is a tyrannosauroid).

The phylogeny I generated for my PhD thesis led me to think that Mirischia might be a tyrannosauroid… in which case Aristosuchus might also be a tyrannosauroid. This isn’t supported, however, in the in-prep Eotyrannus study I’ve co-authored with Andrea Cau. Image: Darren Naish.

I formally suggested a tyrannosauroid identity for Calamosaurus in a 2011 review of Wealden theropods (Naish 2011) but opted to keep Aristosuchus as a compsognathid on account of its similarity with Mirischia from Brazil. However, Mirischia also looks tyrannosauroid-like in some details (it has an anterodorsal concavity on the ilium) and I’ve sometimes wondered if it might also be a member of this clade. Recent results, however, do not support this possibility.

Aristosuchus pusillus is known from a sacrum and its conjoined pubic bones, which possess a notably long, narrow pubic boot (shown in ventral view in the image at bottom right). At left, we see where these bones would fit within the animal (here portrayed as a corpse; the reconstruction is dated and was produced for a conference poster I presented in 1999). Images: Darren Naish, Owen (1876).

So… Calamosaurus, are you a tyrannosauroid or not? When you only have two cervical vertebrae to go on (plus some tibiae that may or may not from the same taxon), it’s about impossible to say, and you can’t resolve things until you have better material. Like, an associated skeleton.

At left, one of the two holotype Calamosaurus foxi vertebrae in multiple views (from Naish et al. 2001). The bone is about 40 mm long in total. At right, a schematic reconstruction showing the two vertebrae in place in the cervical column of a compsognathid- or tyrannosauroid-like coelurosaur (from Naish 2002). Scale bar = 50 mm.

On that note, long-time readers might also recall my mention of a fairly good, associated skeleton of what appears to be a small Wealden tyrannosauroid. But it’s in private hands. I’ve been told by a British palaeontologist that the specimen concerned won’t be available for “this generation” of dinosaur specialists and I should simply forget about it. That’s hard, really hard.

And that’s where we’ll stop now. A second part to this article will be published soon.

For previous TetZoo articles on Wealden theropods and other dinosaurs, see (linking here to wayback machine versions due to destruction or paywalling of everything at versions 2 and 3)…

Of Becklespinax and Valdoraptor, October 2007

The world’s most amazing sauropod, November 2007

Oh no, not another new Wealden theropod!, June 2009

Concavenator: an incredible allosauroid with a weird sail (or hump)... and proto-feathers?, September 2010

The Wealden Bible: English Wealden Fossils, 2011, November 2011

Ostrich dinosaurs invade Europe! Or do they?, June 2014 (every archived version of this article lacks the original illustrations, sorry)

Refs - -

Allain, R., Vullo, R., Le Loeuff, J. & Tournepiche, J.-F. 2014. European ornithomimosaurs (Dinosauria, Theropoda): an undetected record. Geologica Acta 12, 127-135.

Galton, P. M. 1971. A primitive dome-headed dinosaur (Ornithischia: Pachycephalosauridae) from the Lower Cretaceous of England and the function of the dome of pachycephalosaurids. Journal of Paleontology 45, 40-47.

Naish. D. 2002. Thecocoelurians, calamosaurs and Europe’s largest sauropod: the latest on the Isle of Wight’s dinosaurs. Dino Press 7, 85-95.

Naish, D. 2010. Pneumaticity, the early years: Wealden Supergroup dinosaurs and the hypothesis of saurischian pneumaticity. In Moody, R. T. J., Buffetaut, E., Naish, D. & Martill, D. M. (eds) Dinosaurs and Other Extinct Saurians: A Historical Perspective. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 343, pp. 229-236.

Naish, D. 2011. Theropod dinosaurs. In Batten, D. J. (ed.) English Wealden Fossils. The Palaeontological Association (London), pp. 526-559.

Naish, D., Hutt, S. & Martill, D. M. 2001. Saurischian dinosaurs 2: Theropods. In Martill, D. M. & Naish, D. (eds) Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight. The Palaeontological Association (London), pp. 242-309.

Naish, D. & Martill, D. M. 2001. Boneheads and horned dinosaurs. In Martill, D. M. & Naish, D. (eds) Dinosaurs of the Isle of Wight. The Palaeontological Association (London), pp. 133-146.

Owen, R. 1876. Monograph of the fossil Reptilia of the Wealden and Purbeck Formations. Supplement 7. Crocodilia (Poikilopleuron), Dinosauria (Chondrosteosaurus). Palaeontographical Society Monograph 30, 1-7.

Watson, S. 1930. Cf. Proodon [sic]. Proceedings of the Isle of Wight Natural History and Archaeology Society 1930, 60-61.

Minuscule Hummingbird-Sized Archaic Birds Existed During the Cretaceous

UPDATE (added 13th March 2020): since I published the article below, two relevant matters have come to attention, both of which have implications for the fossil discussed in the article.

Article at left from New Scientist; article at right from New York Times.

The first is that the extraction of amber from the locations concerned is linked with significant humanitarian issues. These make the continued publication and promotion of Burmese amber fossils look unethical; I was only dimly aware of these when writing the article and now regret my (minor) role in the promotion of this discovery (I did plan to delete the article but, on advice, was encouraged to keep it, but add the disclaimer you’re reading now). You can read about the humanitarian issues here, here and here.

Secondly, a number of experts whose opinions I respect have expressed doubts about the claimed theropod status of the fossil discussed below and have argued that it is more likely a non-dinosaurian reptile, perhaps a drepanosaur or lepidosaur (and maybe even a lizard).

A few artists have already produced speculative life reconstructions of Oculudentavis as a lepidosaur or similar reptile. It would have to be a big-brained, shallow-snouted, big-eyed one. Image: (c) Mette Aumala, used with permission.

I did, of course, consider this sort of thing while writing the article but dismissed my doubts because I assumed that - as a Nature paper - the specimen’s identity was thoroughly checked and re-checked by relevant experts before and during the review process, and that any such doubts had been allayed. At the time of writing, this proposed non-dinosaurian status looks likely and a team of Chinese authors, led by Wang Wei, have just released an article arguing for non-dinosaurian status. I don’t know what’s going to happen next, but let’s see. The original, unmodified article follows below the line…

—————————————————————————————————————————————

If you’ve been paying attention to 21st century palaeontological discoveries you’ll know that our understanding of Cretaceous vertebrate diversity has been much enhanced in recent years by the discovery of animals preserved within amber.

A number of really interesting vertebrate fossils in amber have been published in recent years. Among them are the two partial enantiornithine bird wings shown at left (both from Xing et al. 2016a), and the tiny anguimorph lizard Barlochersaurus winhtini (from Daza et al. 2018). Images: Xing et al. (2016), CC BY 4.0, Daza et al. (2018).

These include lizards and snakes (Daza et al. 2016, 2018), a segment of dinosaur tail originally identified as that of a non-bird theropod (Xing et al. 2016b), and various small birds (e.g., Xing et al. 2016a, 2017, 2018, 2019), all of which belong to the archaic, globally distributed group known as the enantiornithines or opposite birds. Today sees the latest of such discoveries, and it’s the most remarkable announced so far. It is – in fact – among the most remarkable of Mesozoic fossils ever announced, and I say this because of the implications it has for our understanding of Mesozoic vertebrate diversity.

Life reconstruction of Oculudentavis khaungraae Xing et al., 2020, depicting it as a tree-dwelling avialan theropod with partly colourful plumage. Image: (c) Gabriel Ugueto, used with permission.

The fossil in question, described in the pages of Nature by Lida Xing, Jingmai O’Connor and colleagues, is the complete, anatomically pristine but minuscule skull of a maniraptoran theropod – specifically, an archaic bird – named Oculudentavis khaungraae (Xing et al. 2020). The skull is preserved in a small amber block (31.5 x 19.5 x 8.5 mm) dating to the Cenomanian age of the Late Cretaceous (making it about 99 million years old). Like virtually all recently described amber vertebrates, it’s from Myanmar (Xing et al. 2020).

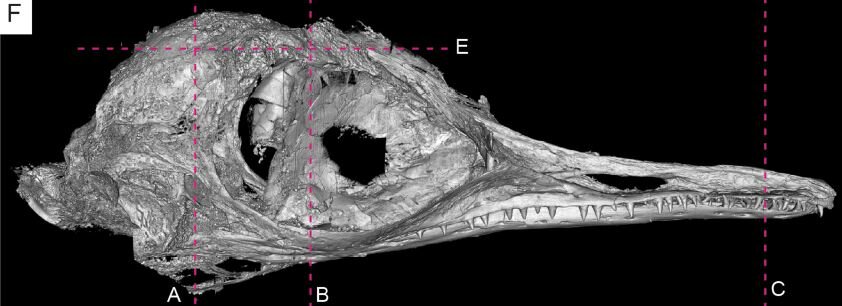

One of several images of the tiny Oculudentavis skull provided by Xing et al. (2020), this one (from their Extended Data) showing the specimen in left lateral view. The scale bar is 2 mm. Image: Xing et al. (2020).

When I say that this fossil is ‘minuscule’, I’m not kidding: the entire skull – the whole skull – is 14 mm long (1.4 cm; not a typo)*. This means that – at a very rough guess – the whole animal was around 90 mm (9 cm) long, an estimate I arrived it by producing a very schematic skeleton which equips the animal with a long tail. Xing et al. (2020) very rightly compare Oculudentavis with small hummingbirds: if it had a long bony tail (which it should have, given its inferred phylogenetic position; read on), it would have been longer than the tiny Mellisuga hummingbirds, the total lengths of which are around 50-60 mm, but not by much. It was unbelievably tiny.

* I’m frustrated by the fact that the authors don’t – so far as I can tell – provide the length of the entire skull anywhere in the paper, nor is there a table of measurements or an effort to estimate the animal’s complete size. Which is weird, because surely this is the most interesting thing about it.

A very rough, semi-schematic skeletal reconstruction of Oculudentavis which I produced in order to gain a rough idea of possible size. As you can see, it would have been tiny. The overall form of the skeleton is based on that of jeholornithiform birds; read on. Image: Darren Naish.

The skull of Oculudentavis has a typical ‘birdy’ look. It has a longish, shallow rostrum, large eye sockets, a lot of bone fusion (no, it isn’t a baby) and a rounded cranium where the section posterior to the eyes is short and compact (Xing et al. 2020). The nostrils are retracted, there’s no trace of an antorbital fenestra, the bony bars beneath the eye sockets bow outwards, and there’s a complete bony bar separating each eye socket from the openings at the back of the skull (Xing et al. 2020).

Digital scan of the skull of Oculudentavis in right lateral view (from the Extended Data of Xing et al. 2020). Note the overall toothiness. The dotted lines here show where slices were recorded during the scanning process. Image: Xing et al. (2020).

It’s a toothy little beast, with an atypically high number of conical (or near-conical) teeth lining its jaws all the way back to beneath the eye socket. This is unusual, since the toothrow in toothed birds and bird-like theropods in general normally stops well anterior to the eye. Another unusual feature is that the teeth aren’t located in sockets but are either fused to the jaw bones (the acrodont condition) or located within grooves that extend along the length of the jaws (the pleurodont condition) (Xing et al. 2020). The teeth look prominent, such that it’s hard to understand how they could be sheathed by lip tissue, nor is any such tissue preserved. Remember that beak tissue doesn’t occur in the same part of the jaws as teeth do, so Oculudentavis wouldn’t have had a true horny covering on its jaws. I assume that it had ‘lip’ tissue sheathing its teeth (except perhaps for the tips of the longest ones), as do other terrestrial tetrapods.

Speculative life reconstruction of Oculudentavis, its feathering and other details inspired by Jeholornis and other archaic members of Avialae. I’ve depicted it on the forest floor but am not necessarily saying that this is where it spent all of its time. Image: Darren Naish.

The eyes are directed laterally and the authors note that Oculudentavis likely didn’t have binocular vision (Xing et al. 2020). The sclerotic rings are huge and fill up most of the eye sockets. Xing et al. (2020) use the relative size of the eyes and their sclerotic rings to make inferences about the activity patterns and visual abilities of this animal: they think that Oculudentavis was likely day-active, had relatively small pupils, and perhaps had “unusual visual capabilities”.

The fossil doesn’t just consist of the animal’s bones alone, because synchrotron scanning reveals the presence of a brain (which is about as wide as it is long). Meanwhile, the bony palate preserves traces of its original tissue covering. This is decorated with numerous papillae, the first time such structures have been reported in a fossil theropod (Xing et al. 2020). The authors also refer to a tongue (!!) but it isn’t possible to make this out in the figures they provide, nor do they label it.

Combined, what do these features tell us about the lifestyle and ecology of Oculudentavis? The well-fused skull, prominent teeth and large eyes suggest that this was a predator, presumably of small arthropods. The soft papillae on the palate are of the wrong sort for fish-eating (Xing et al. 2020). Its tiny size and forest habitat imply that it was arboreal or scansorial – as suggested by Gabriel’s artwork above – but the animals that surround it in the cladogram are mostly terrestrial, so the possibility that it foraged in leaf litter or took regular trips to the forest floor are also conceivable, perhaps. Could it have been a predator of worms, molluscs or even tiny vertebrates, like a dinosaurian shrew?

Oculudentavis would have looked noticeably small relative to other Mesozoic birds, though not absurdly so. It’s compared here with Archaeopteryx (at upper left) and an assortment of others, most of which are enantiornithines. These illustrations are for my in-prep giant textbook project. Image: Darren Naish.

What sort of bird is Oculudentavis? For starters, it’s the presence of fused premaxillary and braincase bones, the position and size of the nostril, eye, postorbital region and domed cranium which strongly indicate that Oculudentavis is a member of Avialae, the bird lineage within Maniraptora (though note that the authors prefer the term Aves for said lineage). They included it within a phylogenetic analysis and found it to be one step more crown-ward (meaning, one node on the cladogram closer to living birds) than is Archaeopteryx, which is surprising because it makes Oculudentavis one of the most archaic members of the bird lineage (Xing et al. 2020). This could mean that birds underwent acute miniaturisation almost as soon as they evolved. Several authors – myself and colleagues included (Lee et al. 2016) – have argued beforehand that theropods on the line to birds underwent a gradual and pervasive decrease in size, but we didn’t (and couldn’t) predict that a size decrease of this sort occurred so early in bird history.

Theropods display a continuous, pervasive decrease in size when we look at the inferred size of ancestral species at successive nodes across the lineage leading to birds. From left to right, this illustration by Davide Bonnadonna shows the ancestral neotheropod (~220 Million years old), the ancestral tetanuran (~200 myo), the ancestral coelurosaur (~175 myo), the ancestral paravian (~165 myo), and Archaeopteryx (150 myo). Image: Davide Bonnadonna.

A World of Tiny Cretaceous Theropods? A key thing here is that we only know about this animal because of its preservation in amber: the rest of the fossil record mostly – the authors suggest – robs us of tiny vertebrates such as this. Could there actually have been many hummingbird-sized miniature theropods of this sort?

Xing et al. (2020) don’t provide a size estimate for Oculudentavis, but they do provide these silhouettes, which show Oculudentavis to scale with a hummingbird and chicken (and part of an ostrich is just visible at far right). Image: Xing et al. (2020).

Here’s where Xing et al.’s (2020) cladogram become especially interesting. The position they propose for Oculudentavis requires that its lineage originated about 150 million years ago, and yet Oculudentavis itself is about 99 million years old. Its lineage, therefore, is at least 50 million years long, in which case there could have been many of these tiny avialan dinosaurs (here, I have to resist the urge to talk about the hypothetical tree-climbing small dinosaurs of Dougal Dixon and George Olshevsky). I emphasise that this speculation assumes that the phylogenetic position Xing et al. (2020) infer is correct; it may not be. Indeed 10% of their trees found Oculudentavis in a different position: within enantiornithines, a possibility which seems ‘more right’ given the identity of other Burmese amber birds. With just a skull to go on, we obviously need more material before we can be especially confident on its phylogenetic position. And on that point, I won’t be surprised if it turns out that Oculudentavis does end up occupying a different position within maniraptoran theropods from the one which Xing et al. (2020) prefer. But none of this affects its minuscule nature, and that’s the real killer point here.

Part of a time-calibrated theropod tree (from Wang & Zhou 2017). According to Xing et al. (2020), Oculudentavis occupies a position more root-ward than Jeholornithiformes, but more crown-ward than Archaeopteryx. If correct, this means that its lineage originated during the latest part of the Jurassic. Image: Wang & Zhou (2017).

What About Other Fossil Vertebrates? If tiny, tiny Cretaceous theropods have remained unknown to us until now, what about other terrestrial vertebrates? I’d always assumed that the truly tiny frogs, lizards and other vertebrates of the modern world – those less than a few centimetres long – were recently evolved novelties of the Cenozoic. But maybe this is completely wrong. Maybe animals of this sort were present in the Mesozoic too, and maybe we’ve missed them due to a size filter which can only be filled by fossils discovered in amber?

The modern world is inhabited by truly tiny lizards and frogs, like this c 3cm SVL Brookesia chameleon and c 1cm Stumpffia frog. Were similarly tiny tetrapods also around in the Cretaceous? Images: (c) Mark D. Scherz, used with permission.

Time will tell. This is really exciting stuff.

For previous TetZoo articles relevant to this one, see…

Bird behaviour, the ‘deep time’ perspective, January 2014

50 million years of incredible shrinking theropod dinosaurs, July 2014

The Romanian Dinosaur Balaur Seems to Be a Flightless Bird, June 2015

The Most Amazing TetZoo-Themed Discoveries of 2018, December 2018

A Multi-Species Nesting Assemblage in the Late Cretaceous of Europe, February 2019

Refs - -

Daza, J. D., Bauer, A. M., Stanley, E. L., Bolet, A., Dickson, B. & Losos, J. B. 2018. An enigmatic miniaturized and attenuate whole lizard from the mid-Cretaceous amber of Myanmar. Breviora 563, 1-18.

Daza, J. D., Stanley, E. L., Wagner, P., Bauer, A. M. & Grimaldi, D. A. 2016. Mid-Cretaceous amber fossils illuminate the past diversity of tropical lizards. Science Advances 2 (3), e1501080.

Wang, M. & Zhou, Z. 2017. The evolution of birds with implications from new fossil evidences. In Maina, J. N. (ed) The Biology of the Avian Respiratory System. Springer International Publishing, pp. 1-26.

Xing, L., McKellar, R. C., O’Connor, J. K., Bai, M., Tseng, K. & Chiappe, L. M. 2019. A fully feathered enantiornithine foot and wing fragment preserved in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber. Scientific Reports 9, 927.

Xing, L., McKellar, R. C., Wang, M., Bai, M., O’Connor, J. K., Benton, M. J., Zhang, J., Wang, Y., Tseng, K., Lockley, M. G., Li, G., Zhang, Z. & Xu, X. 2016a. Mummified precocial bird wings in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber. Nature Communications 7, 12089.

Xing, L., McKellar, R. C., Xu, X., Li, G., Bai, M., Scott Persons IV, W., Miyashita, T., Benton, M. J., Zhang. J., Wolfe, A. P., Yi, Q., Tseng, K., Ran, H. & Currie, P. J. 2016b. A feathered dinosaur tail with primitive plumage trapped in mid-Cretaceous amber. Current Biology 26, 3352-3360.

Xing, L., O’Connor, J. K., McKellar, R. C., Chiappe, L. M., Bai, M., Tseng, K., Zhang, J., Yang, H., Fang, J. & Li, G. 2018. A flattened enantiornithine in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber: morphology and preservation. Science Bulletin 63, 235-243.

Xing, L., O’Connor, J. K., McKellar, R. C., Chiappe, L. M., Tseng, K., Li, G. & Bai, M. 2017. A mid-Cretaceous enantiornithine (Aves) hatchling preserved in Burmese amber with unusual plumage. Gondwana Research 49, 264-277.

Xing, L., O’Connor, J. K., Schmitz, L., Chiappe, L. M. McKellar, R. C., Yi, Q. & Li, G. 2020. Hummingbird-sized dinosaur from the Cretaceous period of Myanmar. Nature 579, 245-249.

Did Dinosaurs and Pterosaurs 'Glow'? Extinct Archosaurs and the Capacity for Photoluminescent Visual Displays

One of many exciting discoveries made in tetrapod biology in recent decades is that UV-sensitive vision is not just a thing that exists, but a thing that’s widespread.

Caption: would a live dinosaur - like this heterodontosaur - look utterly different if its tissues were photoluminescent? Brian Engh explored this possibility in this excellent piece of art, included in Woodruff et al. (2020). Image: Brian Engh.

We’ve known since the early 1980s that at least some birds can detect UV wavelengths, and research published more recently has demonstrated its presence in lizards of disparate lineages, in turtles, rodents and, most recently, amphibians. Some of these animals use their UV-sensitive vision to find food (like pollen-rich flowers) and perhaps even to navigate their environments (UV-sensitive vision in certain forest-dwelling birds might enhance their ability to see certain kinds of leaves, for example).

That’s great, but what’s even more surprising – though maybe it shouldn’t be – is that markings and tissue types in some of these animals are visible to other animals with UV-sensitive vision. Furthermore, some tissue types are able to absorb UV and re-emit it within part of the spectrum visible to we humans. It’s this aspect of the UV story – the possibility that UV is absorbed and emitted as visible light (typically blue light) – that we’re talking about hereon, not UV-sensitive vision. Note that the terms used for this phenomenon are slightly contentious among relevant experts. Most agree that the right term is fluorescence whereas others (including my colleague Jamie Dunning) argue that we should use the more specific photoluminescence. I have no proverbial dog in this fight but am going to stick with photoluminescence here seeing as it’s the one we used in the relevant paper.

Caption: in 2018, Jamie Dunning and colleagues reported the discovery of photoluminescence in puffins. Image: (c) Jamie Dunning.

The discovery of photoluminescence in animals is evidently of broad general interest, and I can make this assertion because several recent studies reporting its occurrence have received an unusual amount of public interest. Dunning et al.’s (2018) report on its occurrence in the brightly coloured bill plates of puffins, for example, proved a really popular discovery (Wikinson et al. (2019) followed up with a subsequent study on the keratinous horns of rhinoceros auklets), as did Prötzel et al.’s (2018) discovery of photoluminescent bones in chameleons. Remarkably, Prötzel et al. (2018) were able to show that the ‘glowing’ bones of these lizards are visible through the skin. At the time of writing, a study reporting widespread photoluminescence in living amphibians has just appeared, and it too has received a fair amount of general interest.

Here it’s worth making a critical point on the popularity of these studies in the popular media. There’s no doubt that this stuff is interesting, and certainly of relevance to biologists at large (for one thing, knowing about the distribution of fluorescence/photoluminescence could have all kinds of implications for surveying and collecting). But there’s concern that the studies are being framed in the wrong way, and that more thorough vetting is needed, in places. Also worth noting is that what role photoluminescence actually has to the animals that emit it is controversial, since some workers argue (a) that its visual signalling role hasn’t been sufficiently tested for, and (b) it may simply be too subtle to be of much use to the animals in which it’s present. Keep this in mind when reading the following!

Caption: Prötzel et al.’s (2018) bone-glow research on chameleons shows that the photoluminescing bones of these lizards were actually visible through the skin. Image: David Prötzel.

These caveats notwithstanding, if UV-themed visual displays are widespread in tetrapods, those of us interested in fossil animals are presented with an interesting set of possibilities. We already think that the many extravagant structures of non-bird dinosaurs and pterosaurs – they include cranial horns, crests and casques as well as spikes, spines, sails, bony plates and so on – functioned predominantly in visual display. Could they also have been photoluminescent, and could this have then been used to enhance the display function of the structures in question?

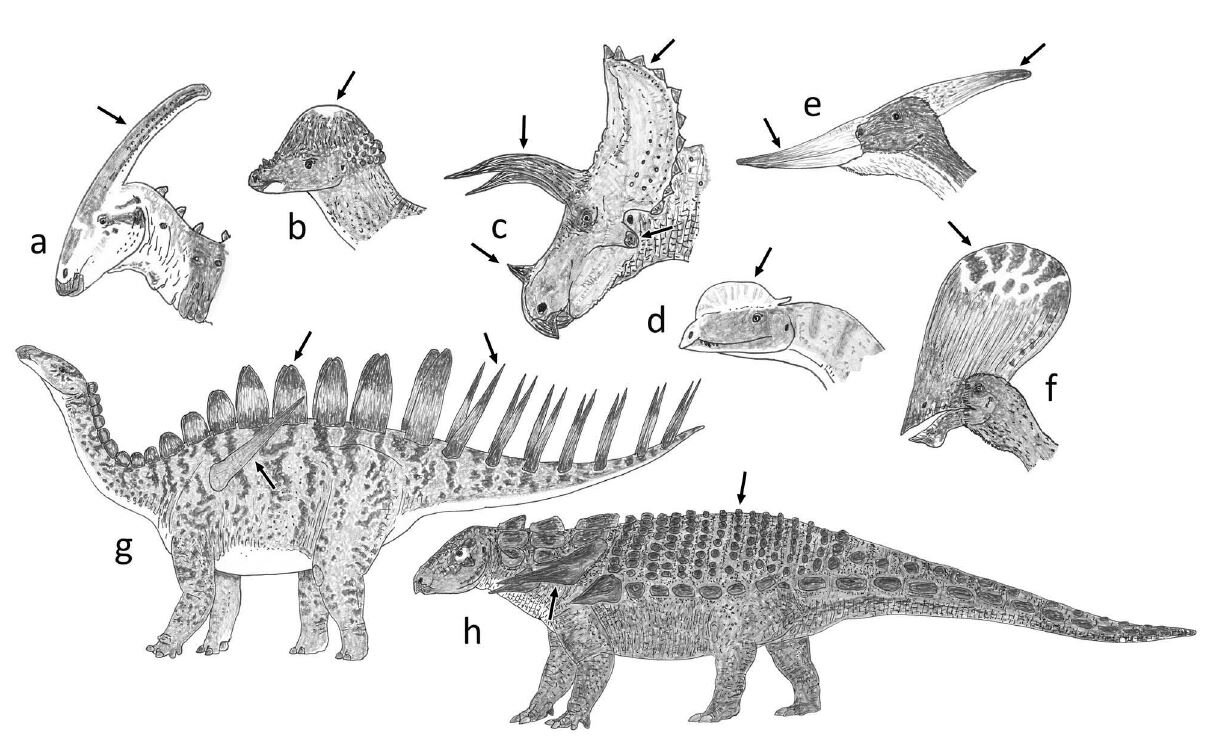

Caption: dinosaurs and pterosaurs are of course notable for their remarkable variety of what I term extravagant structures, a selection of which are depicted here. (a) Parasaurolophus, a hadrosaurid ornithopod. (b) Pachycephalosaurus. (c) Triceratops, a ceratopsid ceratopsian. (d) Dilophosaurus, a theropod. (e) Pteranodon and (f) Tupandactylus the pterodactyloid pterosaurs. (g) Miragaia the stegosaur. (h) Edmontonia the nodosaurid ankylosaur. From Woodruff et al. (2020), images by Darren Naish.

In a brand-new paper published this week in Historical Biology (or on its website, anyway), Cary Woodruff, Jamie Dunning and I set out to consider this very question (Woodruff et al. 2020). At the risk of spoiling the surprise I’ll say that we don’t provide a hard or definitive answer; our aim instead is to bring attention to the possibility that photoluminescence might have been present in some of these animals. We encourage the testing of this possibility and suggest some specific ways in which this testing might be performed. Of incidental interest is that our collaboration evolved from a Twitter discussion (which is currently findable here).

Caption: a palaeontologist ponders new papers on photoluminescence, and then gets talking to one of the relevant researchers. And I chimed in as well, sorry. The rest is history…

I should also add that our idea isn’t especially new. Ever since UV-sensitive vision was first reported in birds back in the 1980s, the idea that extinct dinosaurs might have made use of photoluminescence has been mooted (though, let me make the point again: you don’t need UV-sensitive vision to see photoluminescence). I’ve incorporated photoluminescence into more than one dinosaur-themed media project, most recently Dinosaurs in the Wild.

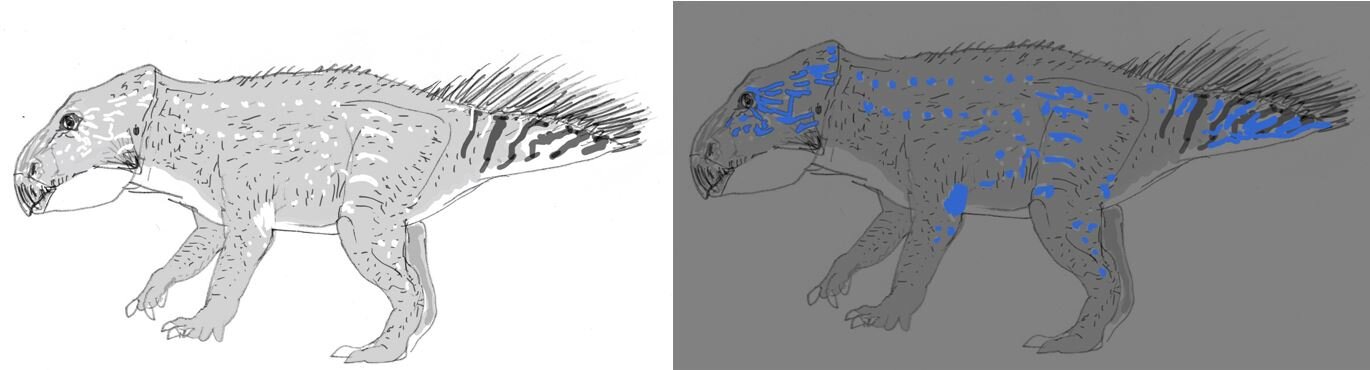

Caption: the idea that Mesozoic dinosaurs might have been exploiting photoluminescence isn’t altogether new. Here are rough sketches I produced depicting the concept of a photoluminescent Leptoceratops produced for the travelling visitor experience Dinosaurs in the Wild. Image: Darren Naish.

A few specific points are worthy of attention. Above, I mentioned Prötzel et al.’s (2018) chameleon-themed ‘bone glow’ study. Bone-based photoluminescence has also been reported in frogs, specifically in the Brachycephalus pumpkin toadlets (Gouette et al. 2019). Could those dinosaurs superficially similar to chameleons (namely ceratopsians: like some chameleons, they have bony frills and prominent horns) also possess bone-based photoluminescence and, if so, could they exploit it in chameleon-like fashion? Well, probably not, mostly because the much larger size of these dinosaurs means that their skin was too thick for this to work (Woodruff et al. 2020).

Caption: for fun, let’s use toy ceratopsians rather than the real things. Could these dinosaurs have had ‘glowing’ bones as modern chameleons do? No, almost certainly not. Image: Darren Naish.

One of the most unusual things about non-bird dinosaurs possessing extravagant structures is that males and females are extremely similar (albeit not necessarily identical) with respect to the form and proportional size of said structures. As regular TetZoo readers might recall from several articles published here within recent years (see links below), some workers interpret the extravagant structures of Mesozoic dinosaurs as functioning within a model of species recognition. According to this model, the structures function as banners used to signal membership of whatever the respective species is. I don’t think that this is valid for a bunch of reasons and in fact I don’t think that extravagant structures have an important role in species recognition at all (Hone & Naish 2013, Knell et al. 2013). An alternative model posits that extravagant structures mostly have an intraspecific function, work as sociosexual signals of reproductive quality, and evolved within the context of sexual selection. This is the model that I and my colleagues support (Hone et al. 2011, Knell et al. 2012, 2013, Hone & Naish 2013), and a lengthy debate that’s been thrashed out in the literature over the past decade pits species recognition and sexual selection as opposing schools of thought.

Caption: at left, mutual sexual selection at play in the Great crested grebe, as illustrated by Julian Huxley in 1914. At right, cover of the famous issue of TREE which includes Knell et al.’s (2012) seminal review.

But if this is so, why is it that ostensible males and females in the dinosaur species concerned are monomorphic: that is, they have similar extravagant structures? Back in 2011, Dave Hone, Innes Cuthill and I argued that these animals might have evolved their extravagant structures within the context of mutual sexual selection (Hone et al. 2011), this being the strategy where both males and females use their extravagant structures in sociosexual display. But while we know that extant monomorphic animals really are monomorphic, we’re not sure that this is (or was) the case for extinct ones: it could still be that their structures differed in hue, colour or some other visual property. If we’re speculating about the possible presence of photoluminescence in extinct archosaurs, the possibility exists that “monomorphic elaborate structures in pterosaurs and non-bird dinosaurs were not monomorphic in life” but differed in how they photoluminesced (Woodruff et al. 2020, p. 5). We were inspired by the sexually dimorphic photoluminescence of chameleons and Brachycephalus frogs.

Caption: could the in-situ, fully intact armour of ankylosaurs like that of the amazing holotype of Borealopelta, shown here, give insight into the potential of photoluminescence in these animals? Image: CC SA 4.0, original here.

Finally… speculating about the presence of photoluminescence is all very well and good, but can we test for it? In those cases where part of the integument is preserved, we can, by shining blacklights at the respective specimens. The problem, however, is that we might not be seeing the original light-emitting properties of the animal. Seemingly positive results might be a consequence of the fact that various tissues (bone included), minerals and preservatives fluoresce under UV (Woodruff et al. 2020).

As a preliminary test, we looked at the osteoderms of the spectacularly preserved ankylosaurs Borealopelta and Zuul under UV light… we did get results, but it’s difficult to know what, if anything, these results tell us about any condition present in life (Woodruff et al. 2020). I should add that people have been shining blacklights at fossils for a long time and seeing all kinds of interesting results (hat-tip to the pioneering work of Helmut Tischlinger); in no way are we implying that we’re anything like the first to do this.

Caption: people have been examining fossils with UV light for decades. These images show the Jurassic pterosaur Bellubrunnus roethgaengeri, illuminated via the use of UV. Image: Hone et al. 2012 (original here).

And that about wraps things up for now. As will be clear, our paper is not much more than a preliminary set of speculations and suggestions for further work, and isn’t intended to be an in-depth analysis of the proposal. But – as I see it – that’s ok: the scientific literature really shouldn’t be considered focused on results alone, since review, discussion and valid speculation are valuable and worthy too. I hope you agree.

UPDATE (adding 4th March 2020): this article has been somewhat modified relative to its original version, since a misunderstanding on my part meant that I was previously describing photoluminescence as a phenomenon especially relevant to animals with UV-sensitive vision. Substantial thanks to Michael Bok for his interest and assistance and for sending comments which enabled me to modify the article.

For previous TetZoo articles on the biology and life appearance of Mesozoic dinosaurs and pterosaurs, see (as usual now, linking to wayback machine versions due to vandalism and paywalling of ver 2 and 3)…

Zuniceratops and the early acquisition and alleged dimorphism of ceratopsian brow horns, April 2009

Necks for sex? No thank you, we’re sauropod dinosaurs, May 2011

Did dinosaurs and pterosaurs practise mutual sexual selection?, January 2012

Sexual selection in the fossil record, September 2012

Dinosaurs and their ‘exaggerated structures’: species recognition aids, or sexual display devices?, April 2013

Refs - -

Dunning, J., Diamond, A. W., Christmas, S. E., Cole, E. L., Holberton, R. L., Jackson, H. J., Kelly, K. G., Brown, D., Rojas Rivera, I. & Hanley, D. 2018. Photoluminescence in the bill of the Atlantic Puffin Fratercula arctica. Bird Study 65 (4), 1-4.

Goutte, S., Mason, M.J., Antoniazzi, M.M., Jared, C., Merle, D., Cazes, L., Toledo, L.F., el-Hafci, H., Pallu, S., Portier, H., Schramm, S., Gueriau, P. & Thoury, M. 2019. Intense bone fluorescence reveals hidden patterns in pumpkin toadlets. Scientific Reports 9, 5388.

Prötzel, D., Heß, M., Scherz, M. D., Schwager, M., van’t Padje, A. & Glaw, F. 2018. Widespread bone-based fluorescence in chameleons. Scientific Reports 8, 698.

Wilkinson BP, Johns ME, Warzybok P. 2019. Fluorescent ornamentation in the Rhinoceros auklet Cerorhinca monocerata. Ibis 161, 694-698.

Corucia of the Solomon Islands, Most Amazing of Skinks

SKINKS! Again.

A captive Corucia in a commercial collection. Image: Darren Naish.

Skinks are an enormous, globally distributed group of lizards. As of December 2019, there are around 1685 recognised species, accounting for about 25% of living lizard diversity (there are about 6780 lizard species in total), and – perhaps unsurprisingly – I’ve written about them quite a lot at TetZoo… though it’s now hard to appreciate this, since the articles concerned have variously been vandalised, curtailed or paywalled by the hosters of TetZoo ver 2 and ver 3. See links below for the wayback machine versions of these articles.

There’s a lot about skinks in the TetZoo archives, please see the links below. Thank Christ for wayback machine.

Among the most remarkable and striking of skinks is the large Solomon Islands skink or Monkey-tailed skink Corucia zebrata, a prehensile-tailed, mostly green, arboreal skink, and the only member of its genus (though read on). Not only is this amazing lizard green, arboreal and equipped with a powerful prehensile tail, it’s also a giant, especially big specimens reaching 72 cm in total length. This makes it the biggest known skink. It first became known to science in 1856 when indefatigable taxonomist John E. Gray tersely described specimens brought to London by John MacGillivray after his voyage aboard the HMS Herald, the type specimens coming specifically from San Christoval (today termed San Cristobal or Makira) in the Solomon Islands (Gray 1856).

The Solomon Islands. Image by OCHA (original here), CC BY 3.0.

The lizards appear widespread throughout the archipelago (Makira is one of the most southerly islands there) and are variable, differing in eye colour, size, and in the configuration and size of their scales. Some experts think that subspecies should be named to reflect this variation, and the smaller, paler-eyed northern form was named C. z. alfredschmidti in 1997 (Köhler 1997). Maverick Australian bad boy herpetologist Raymond Hoser has claimed the existence of several entirely new species of Corucia, one of which he named for his mother. If you want to know more about Mr Hoser (and why he’s a total joke) see the TetZoo article here.

A captive Corucia in a private collection. Note the dark irides which make this individual look different from some of the other animals shown here. Image: S. Hilgers.

So far, all published work on the phylogeography and variation within Corucia finds it and its divergences to be young; as in, younger than about 4 million years old (Hagen et al. 2012). Yet it must have diverged from its closest living relatives 20 million years ago or more (we can infer this because fossils of other members of the same skink group are this old or older), meaning that the vast bulk of its lineages’ history remains completely unknown, for now.

Gray described Corucia as a new member of the ‘fish-scaled’ skink group. This seems a bit odd today, because we don’t refer to any skink by this moniker (to my knowledge). He evidently regarded it as part of the Australasian skink group that includes Egernia, Tiliqua (the blue-tongues) and kin though. Today we think (on the basis of molecular phylogenetics) that this is correct, and that Corucia is a lygosomine skink (Skinner et al. 2011, Pyron et al. 2013).

Representatives of most (but not all) of the skink lineages currently regarded as ‘families’ by Hedges and colleagues. 1: Mabuya, of Mabuyidae. 2: Acontias, of Acontidae (I think it should really be Acontiidae). 3: Ristella, of Ristellidae. 4: Scincus, of Scincidae. 5: Lygosoma, of Lygosomidae. 6: Egernia, of Egerniidae. 7: Eugongylus, of Eugongylidae. These images are from my in-prep textbook, progress of which can be observed here. Images: Darren Naish.

Traditionally, all skinks are combined in the single family Scincidae. Most herpetologists argue that we should stick with this taxonomic system since there’s no dispute that Scincidae is a clade and thus no real need to shake things up. But some argue that putting all the species of this enormous, complex group into the same single ‘family’ obscures and under-emphasises its diversity and disparity and that it would be more realistic to split it into a whole bunch of families (nine in fact: Acontidae, Atechosauridae, Egerniidae, Eugongylidae, Lygosomidae, Mabuyidae, Ristellidae, Scincidae and Sphenomorphidae) (Hedges & Conn 2012, Hedges 2014). I’ve written about this situation before: see the articles below for more. If we follow this revised family-level classification, Corucia is part of Egerniidae.

Substantially simplified cladogram depicting lygosomine skink phylogeny, mostly based on Pyron et al. (2013). Images (top to bottom): Wolfgang Wuster, H. Zell, $Mathe94$, Benjamint444 (all CC BY-SA 3.0), Mark Stevens (CC BY 2.0), W. A. Djatmiko, S. Caut et al. (both CC BY-SA 3.0).

The name Corucia is derived from ‘coruscus’ (meaning shimmering, and referring to the shiny scales), while zebrata is a reference to the stripes present in the specimens Gray was familiar with. Given that Solomon Islanders know this lizard and eat it, there was and is surely indigenous knowledge of the species and probably lore about it, though I haven’t encountered such so far. It’s generic name shouldn’t be confused with that of the Cretaceous fossil lizard Carusia, a possible relative of the living xenosaurids.

Here in the UK, it’s currently not difficult to encounter Corucia in captivity. I should add that it does well if conditions are right: as a canopy-dwelling lizard it needs tall branches with suitable retreats, and some collections (most notably the Philadelphia Zoo) have been breeding Corucia for over 40 years now. They’re not especially active during peak visitor time at zoos, mostly because they’re crepuscular. They’re also exclusively herbivorous and are in fact the only skinks said to be committed to a plant diet. Leaves, shoots, flowers and fruit are all consumed, including those of toxic species. Their dung has a distinctive aroma and it’s apparently possible to locate trees inhabited by this species by smell alone: Harmon (2002) used this technique, making his study “the first documented use of olfactory cues to locate skinks in the wild” (p. 177).

Fine side-eye from this captive Corucia at Bristol Zoo, UK. Image: Darren Naish.

Corucia is viviparous with a 6 to 8 month gestation, but the big deal about its viviparous strategy is that its babies are proportionally enormous, being about half the size of the mother. They can be over 30 cm long and weigh 175 g. Unsurprisingly, only a single baby is normally produced, though rare cases of twins and triplets are on record.

Corucia is also a social skink. In this, it’s far from unique, since egerniids of more than 20 species live together in family groups and even exhibit monogamy, kin recognition, colonial living and co-operation. Juvenile Corucia sometimes stay with their parental group for an extended period and mothers are reported to be highly protective of newborn juveniles (Wright 2007), which is what theory predicts given the substantial material investment involved in growing such a large baby. Also interesting is that not all the adults which form social groups in this species appear related (Wright 1996), and that Corucia groups are even known to allow orphaned juveniles to join their groups (read on…). Some juveniles do apparently leave their parental group to join others (Wright 2007).

Dark-eyed captive Corucia, and here’s proof that this arboreal lizard will - in captivity - drink from standing water (at least some arboreal lizards don’t do this, they rely only on water droplets on leaves). Image: S. Hilger.

Studies of wild-living Corucia on Ugi Island in the Solomon archipelago showed that individuals living less than 150 m apart were likely to be related, but also that individuals wandered for several kilometres (Hagen et al. 2013). Telemetry results obtained in an earlier study (Hagen 2011) indicate that this sort of dispersal is unusual, however, given that Corucia is mostly sedentary with home ranges being equivalent to the canopy of a single tree. Maybe this explains why groups are apparently happy to ‘adopt’ lone youngsters – they may well be related to the members of the group already. After all, we know that kin selection is at play elsewhere in social egerniids.

One of the latest papers discussing social behaviour in these skinks is also among the most shocking, since it reports the occurrence of a Corucia group living together in a deep tree hole, and one that was flooded at its bottom. Remarkably, some of the Corucia in the hole were fully submerged and located beneath the water surface at the time of discovery. To my supreme frustration, I can’t locate this publication right now, even though I recall downloading it (it was a short note in, perhaps, Salamandra or Journal of Herpetology). Let me know if you know the paper concerned. It was such a bizarre report that more information is needed. And I guarantee that it’s legit and that I didn’t dream it.

A captive Corucia at Bristol Zoo. Note the sharply curved claws and interesting nose in these lizards. Image: Darren Naish.

Finally, what does the future hold for this amazing lizard? Unsustainable destruction of forests on the Solomon Islands poses a problem, as does local hunting for the pot and collecting for the pet trade: between 1992 and 1995, 12000 animals were exported for this reason, mostly to the USA (Mann & Meek 2004). Consequently, Corucia is now being considered for inclusion on Appendix I of CITES, with captive breeding likely being crucial to its persistence.

Another captive Corucia. This image is useful and interesting because it shows the cross-sectional shape of the body: note that the side of the body is flat and that there’s an obvious change in angle between the side and dorsal surface. Image: TimVickers (original here), public domain.

A giant, fully herbivorous, slow-breeding, social skink is such a special animal that we must make effort to ensure its survival into the future. And that’s where we must end.

For previous TetZoo articles on skinks, see…

Mystery emo skinks of Tonga!, October 2010

Isopachys: worm-like skinks from Thailand and Myanmar, November 2010

Hammer-toothed skink SMASH!, November 2012

Skinks, Skinks, Skinks!, October 2014

Terror skinks, social skinks, crocodile skinks, monkey-tailed skinks… it's about skinks (skinks part II), October 2014

Sandfishes and kin: of sand-swimming, placentation, and limb and digit reduction (skinks part III), November 2014

The Madagascan Skink Amphiglossus Eats Crabs, February 2016

Refs - -

Gray, J. E. 1856. New genus of fish-scaled lizards (Scissosarae) from New Guinea. Annals and Magazine of Natural History (2) 18: 345-346.

Hagen, I. J. 2011. Home ranges in the trees: radiotelemetry of the Prehensile tailed skink, Corucia zebrata. Journal of Herpetology 45, 36-39.

Hagen, I. J., Donnellan, S. C. & Bull, C. M. 2012. Phylogeography of the prehensile-tailed skink Corucia zebrata on the Solomon Archipelago. Ecology and Evolution 2, 1220-1234.

Hagen, I. J., Herfindal, I., Donnellan, S. C. & Bull, C. M. 2013. Fine scale genetic structure in a population of the prehensile tailed skink, Corucia zebrata. Journal of Herpetology 47, 308-313.

Harmon, L. J. 2002. Some observations of the natural history of the Prehensile-tailed skink, Corucia zebrata, in the Solomon Islands. Herpetological Review 33, 177-179.

Hedges, S. B. 2014. The high-level classification of skinks (Reptilia, Squamata, Scincomorpha). Zootaxa 3765, 317-338.

Hedges, S. B . & Conn, C. E. 2012. A new skink fauna from Caribbean islands (Squamata, Mabuyidae, Mabuyinae). Zootaxa 3288, 1-244.

Köhler, G. 1997. Eine neue Unterart des Wickelschwanzskinkes Corucia zebrata von Bougainvillle, Papua-Neuguinea. Salamandra 33 (1), 61-68.

Mann, S. L. & Meek, R. 2004. Understanding the relationship between body temperatureand activity patterns in the giant Solomon Island skink, Corucia zebrata, as a contribution to the effectiveness of captive breeding programmes. Applied Herpetology 1, 287-298.

Pyron, R. A., Burbrink, F. T. & Wiens, J. J. 2013. A phylogeny and revised classification of Squamata, including 4161 species of lizards and snakes. BMC Evolutionary Biology 2013, 13:93.

Skinner, A., Hugall, A. F. & Hutchinson, M. N. 2011. Lygosomine phylogeny and the origins of Australian scincid lizards. Journal of Biogeography 38, 1044-1058.

Wright, K. 1996. The Solomon Islands skink. Reptile & Amphibian Magazine 3 (2), 10-19.

Wright, K. M. 2007. Captivating giants. Reptiles Magazine 15 (12), 54-68.

Beautiful, Big, Bold Dinosaur Books: of Molina-Pérez and Larramendi’s Theropods, Rey’s Extreme Dinosaurs 2, and Parker et al.’s Saurian

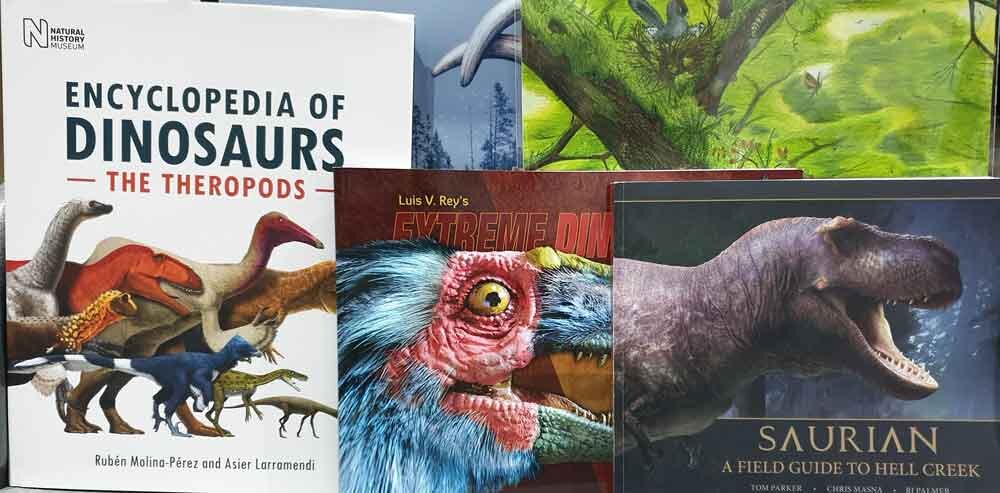

One of the reasons you read TetZoo is because of the dinosaurs, and among the dinosaur-themed things I write about on fairly regular basis are new(ish) dinosaur-themed books.

Partly because I’m way overdue on the book reviews I planned to write during 2019, I’m here going to talk about some recently-ish published dinosaur-themed books that you’d do well to buy and read, if you wish, or can. I’ve written about recently-ish published dinosaur-themed books on quite a few recent occasions; see the links below for more. Let’s get to it.

Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs: the Theropods, by Rubén Molina-Pérez and Asier Larramendi

I can say right out of the gate that this 2019 work is one of the most spectacular dinosaur-themed works that has ever seen print. Think about that for a minute, since it’s a pretty grand claim. Yes. This book is spectacular: big (288 pages, and 24.5 cm x 30 cm), of extremely high standard, packed with information, and containing a vast number of excellent and highly accurate colour life reconstructions. Originally published in Spanish, it has now been translated (by David Connolly and Gonzalo Ángel Ramírez Cruz) and published in English by London’s Natural History Museum. The book consists of eight sections, which variously go through the theropod cladogram, discuss geographical regions and the theropods associated with them, and review theropod anatomy, eggs, footprints and so on. And it’s packed with excellent illustrations… hundreds of them.

A selection of pages from Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2019). At left, eggs depicted to scale (with a basketball). At right, just two of the many pages that feature theropod skeletal elements. Images: Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2019).

The art is great – the majority of colour images being by the phenomenally good and reliable Andrey Atuchin – and I’d recommend that anyone interested in the life appearance of dinosaurs obtain the book for its art alone. I have one criticism of the art though, which is that the colour schemes and patterns used for some of the animals are occasionally based on those of living animals (most typically birds).

Just two of the many UNNAMED theropod species reconstructed in the book. Exciting stuff! The humans that feature in the book are an interesting lot. Images: Molina-Pérez & Larramendi (2019).